Scientists have revealed that the native oyster ecosystem has declined to the extent that it has been declared ‘collapsed’, highlighting the importance of ambitious restoration initiatives across Europe.

Using the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems Framework, a new study has concluded the European native oyster reef ecosystem type is collapsed, with no locations remaining in Europe where the habitat (high densities of oysters) extends beyond 0.1ha.

Historically, oyster reef ecosystems persisted at large scales (several km2), with individual reefs within the ecosystems present at the scale of several hectares. While this work confirms the absolute degradation of this critical marine ecosystem in Europe, it also serves to highlight the potential benefits of investing in large scale ecosystem recovery.

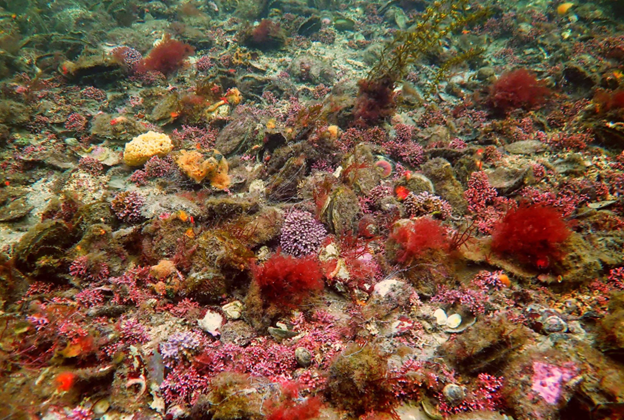

Photo: Dr Jose M. Fariñas-Franco

The assessment, led by international conservation charity ZSL and the University of Edinburgh, and supported by researchers across Europe, reviewed historical and ecological data intending to define the extent of the European native oyster ecosystem.

Scientists have revealed that thriving oyster reef ecosystems are nothing like those seen in European seas today. Newly compiled historical data shows these complex three-dimensional oyster reefs once grew to the size of a football pitch and collectively covered an area of over 1.7 million hectares, an area larger than Greater London.

They would have hosted a diverse, abundant and flourishing community of fish, crabs, starfish, and birds, such as the distinctive oystercatchers – named for their preference for feeding on oysters. The ecosystems were often called the temperate equivalent of tropical coral reefs. Healthy oyster reefs are vital habitats for many species and have a huge impact on the environment around them. They provide food for people, stabilise shorelines, cycle nutrients, and filter water —a single adult oyster filters up to 200 litres of water daily.

Current definitions of the habitat specify a handful of oysters on the seafloor as their defining feature compared to their historical vibrancy. Therefore, a lack of an ecologically meaningful baseline and accurate definition has hampered current efforts to restore reef ecosystems. The ecosystem red listing, while it delivers bad news about the habitat’s current status, should serve as a catalyst for greater ambition in ecosystem recovery.

Illustration of what the undulating seabed may have looked like from historical descriptions ©Maria Eggertsen

“The ecosystem has been lost from living memory, and the benefits it provided have only just been realised now it is almost too late. The stark contrast between the modern-day flat seabed and historical data must act as a wake-up call for action to restore the once-thriving marine environments,” said Alison Debney, ZSL Conservation Lead, Wetland Ecosystem Restoration and co-founder of the Native Oyster Network UK & Ireland.

European oyster reef habitats are now so scattered and degraded that, except for a few locations such as Norway and Sweden, oysters are largely found in isolation or in tiny clumps.

“With the collapse of the native oyster ecosystem across Europe, we’ve also lost an enormous filtration engine in the NE Atlantic due to oysters’ role in filtering seawater and removing nutrients. Possibly even more stark is the loss of biodiversity that preyed or lived on these reefs and the organisms that inhabited them,” said Joanne Preston, Professor of Marine Biology, University of Portsmouth and co-founder of the Native Oyster Network UK & Ireland.

Small clock formation of native oysters on the seabed ©Stéphane Pouvreau / Ifremer

“Given time and space, nature can recover. As a habitat-creating species, restoring native oyster habitat could potentially trigger a cascade of recovery for other species, offering a beacon of hope in the face of collapse. However, it will not be a quick fix as oyster reefs are slow to generate, with layers of new oysters building up on the dead shells of their predecessors,” said Alison Debney.

“Piecing the historical data together with data from current restoration and recovery efforts, we were able to define the original structure and function of the native oyster reef ecosystem. We were shocked by our findings.” said Dr Philine zu Ermgassen of the University of Edinburgh.

“While UK and EU Restoration efforts are a commendable starting point, a cross-sector approach is needed to halt destructive activities. Small-scale restoration projects are valuable, but true ecosystem recovery requires systemic processes and sustainable financing.” said Dr zu Ermgassen.

The full journal paper, ‘European Native Oyster Reef Ecosystems Are Universally Collapsed’, is available online.